Discovery and Publication

Discovery

East of the city of Jerusalem, the mountainous landscape plummets dramatically 1200 meters to the lowest point on earth, the Dead Sea. Some of the most dramatic biblical stories are set in the rocky caves of this region, between the Judean hills and the Dead Sea. Here, in the intense heat of the barren Judean Desert, we can visualize David fleeing from King Saul seeking refuge in the desert’s mountain caves, and Jesus rejecting the temptations of the devil. For thousands of years the Judean Desert held secrets buried in its sands, only to be revealed by a young Bedouin shepherd in 1947. The discovery of these ancient treasures initiated a modern-day adventure into the past, revolutionizing our understanding of history and religion.

As the story goes, a shepherd of the Ta'amireh tribe left his flock of sheep and goats to search for a stray. Amid the crumbling limestone cliffs that line the northwestern rim of the Dead Sea, around the site of Qumran, he found a cave in the crevice of a steep rocky hillside. Intrigued, he cast a stone into the dark interior, only to be startled by the sound of breaking pots. This sound echoed around the world. For he had stumbled on the greatest find of the century, the Dead Sea Scrolls. Upon entering the cave, the young Bedouin found a mysterious collection of large clay jars. The majority were empty and upon examining the remaining few, he found that the jars were intact, with lids still in place. However, a closer look revealed nothing but old scrolls, some wrapped in linen and blackened with age.

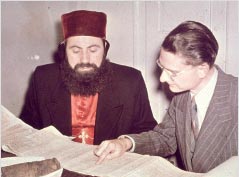

He and several companions brought the scrolls to Kando, a Bethlehem antiquities dealer, for appraisal. Intrigued by the findings, Kando sent the Bedouin back to the caves in search of more treasures. To his delight, they returned with a total of seven scrolls. Blind to their real value, the Bedouin sold four of the seven scrolls to Kando and three to a second antiquities dealer named Salahi. Kando then resold the four scrolls to Archbishop Samuel, head of the Syrian Orthodox Monastery of St. Mark in Jerusalem.

When Hebrew University Professor Eliezer Lipa Sukenik caught wind of the Scrolls’ discovery through an Armenian antiquities dealer, he set out to investigate the significance of the finds. Braving Arab-Jewish tensions, he travelled to meet the Armenian dealer at the British divided military zone of the Jerusalem border. In this clandestine meeting, the dealer held up a fragment of leather for the professor to examine. As Sukenik peered through the wire, he recognized the ancient writing.

Eager to see more, Sukenik travelled with the dealer to Bethlehem to see Salahi, who was in the possession of three Scrolls. Opening the Scrolls, he was amazed to see Hebrew manuscripts, one thousand years older then any existing biblical text. In his diary, Sukenik recollected:

“ My hands shook as I started to unwrap one of them. I read a few sentences. It was written in beautiful biblical Hebrew. The language was like that of the Psalms, but the text was unknown to me. I looked and looked, and I suddenly had the feeling that I was privileged by destiny to gaze upon a Hebrew Scroll which had not been read for more than 2,000 years. ”

The First Seven Scrolls

1948: The first three works under the care of St. Mark’s Monastery (a complete manuscript of the book of Isaiah, a sectarian work called the Community Rule, and a commentary on the book of Habakkuk) are photographed by John C. Trever, then director of Jerusalem’s American Schools of Oriental Research. Sukenik acquires and publishes selections of three Scrolls: The War Scroll, the Thanksgiving Scroll (Hodayot), and a second copy of Isaiah.

1949: Regional turmoil leads Syrian Archbishop Samuel to smuggle his precious four Scrolls out of the country, relocating them to a Syrian Church in New Jersey.

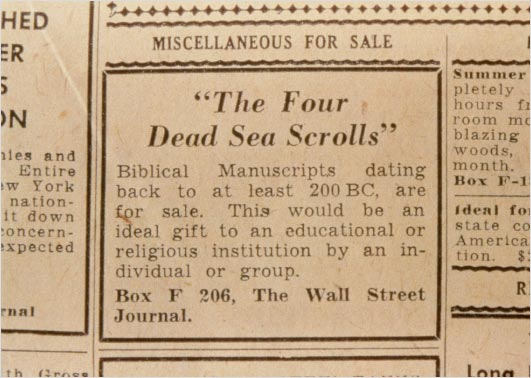

1954: Samuel places the same four Scrolls up for sale in a Wall Street Journal advertisement. Yigael Yadin, son of Professor Sukenik, purchases the four Scrolls through an American middleman, on behalf of the State of Israel.

1955: Yadin joins the four Scrolls with the three already located at the Hebrew University

1965: The "Shrine of the Book" is built to house these seven Scrolls.

Aftermath of Initial Discovery

When word spread that these seven Scrolls contained biblical texts and other ancient religious writings, it opened the way for a series of similar finds in ten other nearby caves over the next nine years. This vast manuscript treasury, known as the "Dead Sea Scrolls", includes a small number of near-complete Scrolls and tens of thousands of Scroll fragments, representing over 900 different texts written in Hebrew, Aramaic and Greek.

Excavation over the years has extended outside the Qumran area, south along the western shore of the Dead Sea, from the caves of Wadi Murabba'at and Nahal Hever to Masada. Additional Scroll fragments have been discovered at numerous sites. Today, all of these Judean Desert manuscripts are collectively known as the Dead Sea Scrolls.

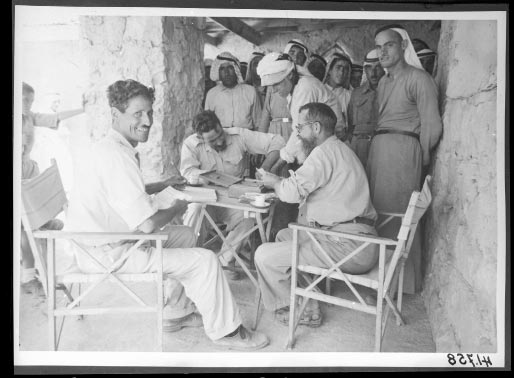

1949- 1956Roland De Vaux, Director of École Biblique et Archéologique Française in East Jerusalem and Gerald Lankester Harding, British Director of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan (DAJ), led the archaeology team surveying the area.

News of the discovery sent archaeologists, as well as Bedouin treasure hunters,

racing to excavate the area where the first Scrolls were found. Overall, they

discovered thousands of Scroll fragments within

10 additional caves—in total the remains of over

900 manuscripts.

Yet it was the Bedouin

who discovered the majority bounty, the richest treasures of the caves. In Cave

4 alone, dug out of the sheer face of an escarpment, thousands of fragments

from about 500 different Scrolls were found. De

Vaux and Harding negotiated with the Bedouin to purchase the Scrolls they had

found. In 1953, Harding and De Vaux appointed an international team of

scholars to begin the publication of the Scrolls. As the team began their work

at the Rockefeller Museum, piecing together the fragments of over 900

manuscripts, a complex historical puzzle emerged.

Publication

For the first 40 years after their discovery, the study of the thousands of text fragments was monopolized by fewer then a dozen international scholars, all great experts in their respective fields. This limited team size prevented the speedy publication of the texts. In the early 1990s, the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) took major steps to advance the publication of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Hebrew University Professor Emanuel Tov was nominated as chief editor and the publication was divided among about 100 international scholars; by 2001, the majority of the official editions had been published and were located in academic libraries.

At the same time, concern for the Scrolls’ physical condition led the IAA to establish a conservation lab dedicated solely to the conservation and preservation of the Scrolls.